The Epic of Competitions That Create Myths

Homer’s poems tell of a competitive ethic and celebrate the personal and social qualities of champions. The political function of the Olympic Games.

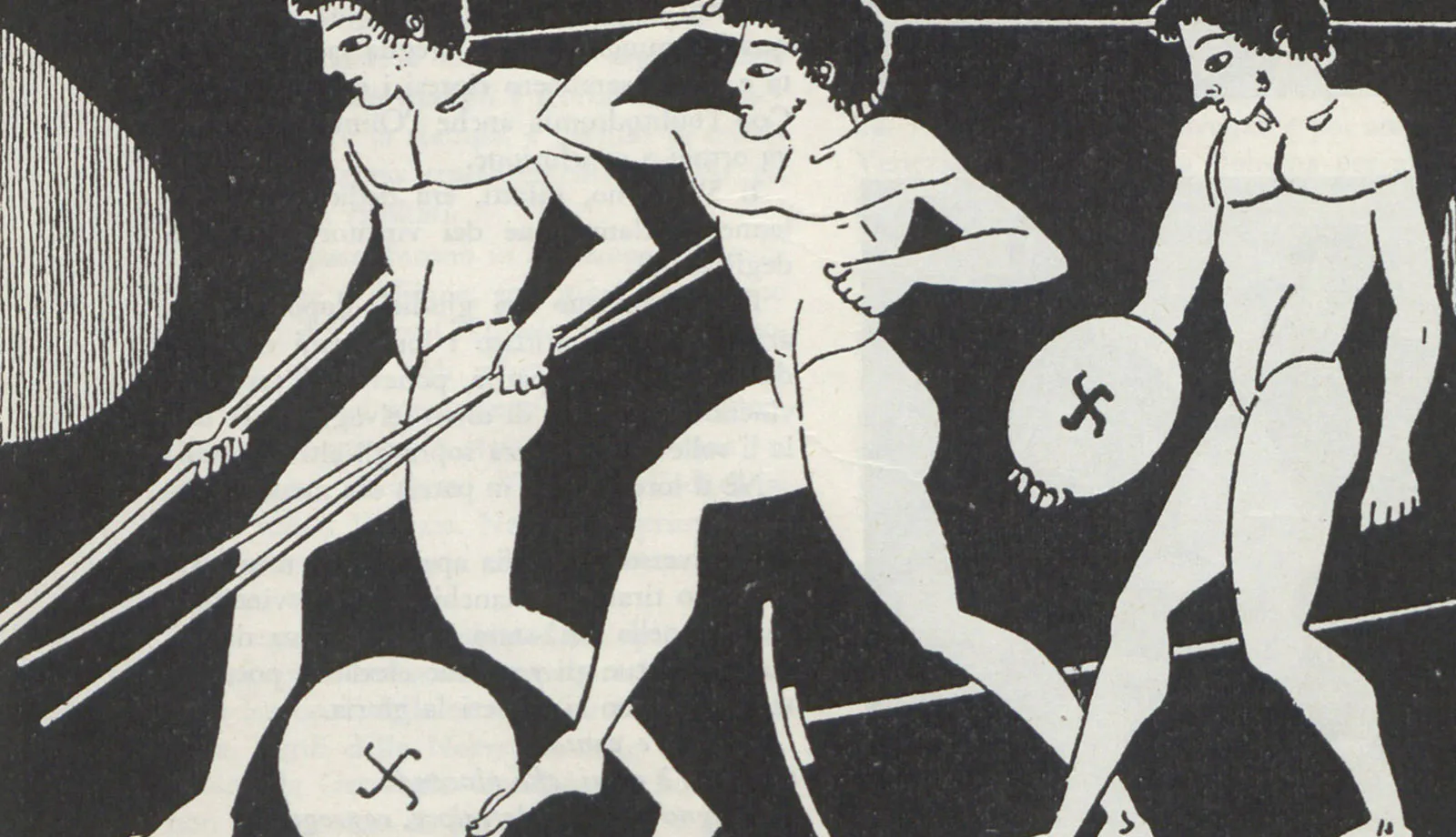

As the Homeric poems show unequivocally, Greek ethics were fundamentally and extremely combative from the beginning.

In the world they describe, the qualities that made someone a hero were those enabling them not just to stand out but to dominate others in all fields, defeating their enemies in war and showing their superiority in social relationships. It is no coincidence that, in the Iliad, the teaching that Peleus gives his son Achilles, who is about to set out for Troy, is to ‘always be the best and superior to others’ (Il. XI, 784). It is no coincidence that Hippolytus the king of the Lycians gave the same advice to his son Glaucus (Il. VI, 208). This was the legacy that fathers passed on to their children from generation to generation. Just how deeply they absorbed it appear in some famous verses by Pindar. Those who had suffered the shame of defeat, he writes, would return home ‘by indirect hidden paths’.

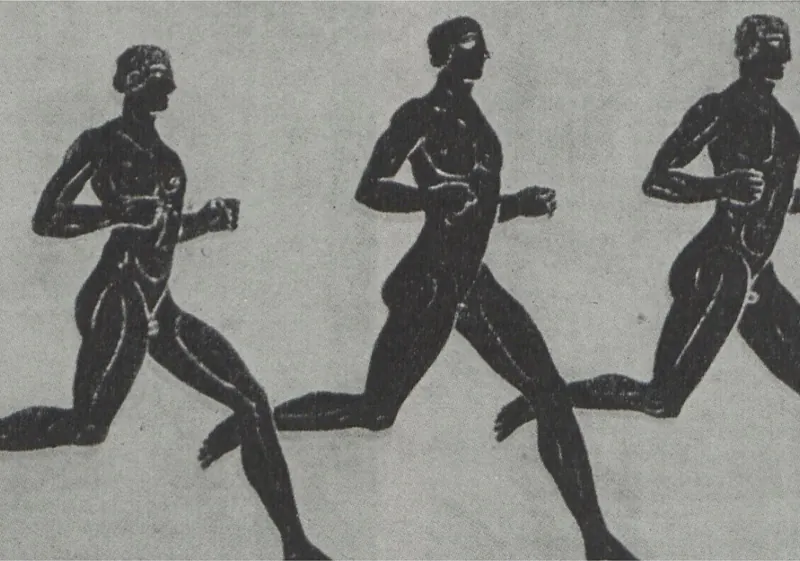

Defeat was a sign of inadequacy, victory of valour. The culture of sport was part of this set of values. The importance that it continued to have through the centuries is shown by the prestige throughout Greece of the athletic games held at regular intervals in the various cities. To understand their fundamental political significance a brief historical digression is necessary.

The games were the occasion when the awareness of belonging to a common system of values and the importance of this bond prevailed over the natural factiousness of the cities, however briefly. This was, in fact, the fundamental political function of the games.

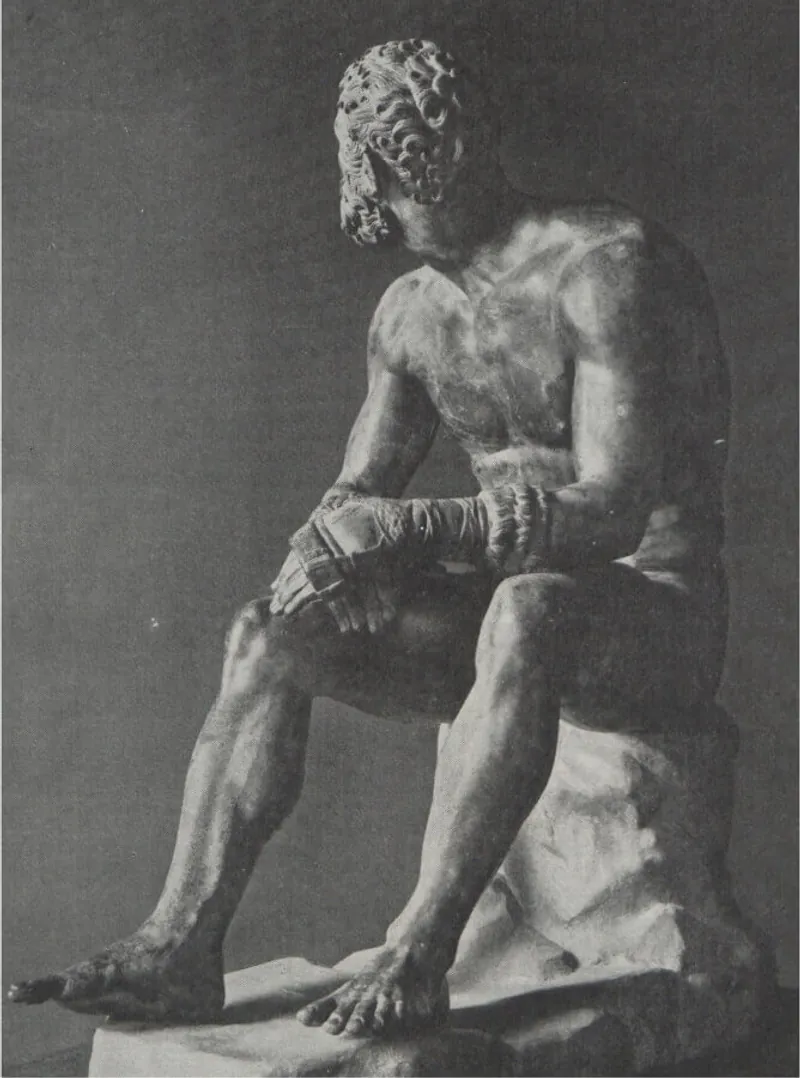

Those who competed in that early phase did so only for the glory. But over time it became customary to pay various honours to the winners, such as giving them free meals for life. Initially the honours were only symbolic, given the high social status of those who could afford to take part in the events. Gradually the prizes and honours were extended, eventually including statues of the victors to be erected in the city of their birth, or commissions to the most renowned poets to compose odes in their honour.